- Home

- P. N. Elrod

Dracula_in_London Page 7

Dracula_in_London Read online

Page 7

She blinked and nodded. After a moment she looked at me again, and there was new strength in her eyes.

"You'll defend my daughter?" she asked. "Against anyone?"

"Yes ma'am."

She took her hand out of the pocket of her nightrobe. She was holding a shining silver paper knife, and she passed it to me and folded my fingers around the warm handle.

"Take it," she said. "Use it if you have to."

I left her and went downstairs to warn Cook that the battle was on.

But Cook was gone. Whether she'd run or been dragged away, we never knew; no trace of her was ever found. Penny had found George and sent him on his way, but as the day dawned, then dragged on, Dr. Seward didn't come. There was no telephone at Hillingham, though the Westenras had one in the London house; I missed it most sorely, because help was miles away. Still, Dr. Seward would come. Surely.

Towards five I sent Kate out to walk into Whitby and find help—the constable, if nothing else. She'd only been gone a few minutes when she came back, screaming like the house was afire, to tell me that George was lying dead, the carriage smashed, on the rocks at the turn of the road. After that I couldn't get any of them to go.

So night fell, and we were all alone. Four maids, two ladies, and Elizabeth Gwydion. But Dr. Van Helsing would be back early in the morning. All we had to do was see daylight again. So I told the others, and so it was.

But it was a terrible long night. Dead quiet outside, not even a breath of wind. Just the crash of the sea in the distance, and the sense that the whole house was holding its breath.

Mrs. Westenra dismissed Elizabeth. Oh, you should have seen the woman's face—cold, haughty, amazed. But Mrs. Westenra was too soft to make the woman leave the house in the dark; she settled for sending her to her room and telling Penny to watch the door.

It was close on midnight when I took Penny a cup of hot cocoa and found the chair outside of Elizabeth Gwydion's room sitting empty, though the seat of it was still warm. And the door open just a crack.

I pushed it to find poor dear Penny lying on the cold wood floor, struggling. She flung out a hand to me. Elizabeth Gwydion had hold of her feet, and stooped over her, like an evil black shadow—

Yes. Him. Dracula. He tore loose of Penny's throat and looked at me, parted bloody lips in a smile, and his teeth were sharp and white, and Elizabeth Gwydion let go of Penny and shot to her feet, grabbed hold of my arms. I cried out and tried to fight but she was horrible strong, and the stale smell of her, the rotting stench of him, made me faint and sick.

I suppose what saved me was the crucifix, which I'd mended and still had hung around my neck. It swung free and caught the light, sending Dracula reeling back. Remember that I told you I never saw him make himself dog or wolf or bat? I saw him turn to a stinking black mist like flies that whipped away through the open window. At the time I thought he was afraid of me. Now I think it was just that he was impatient to be about his other business.

Elizabeth still had hold of me. She was fearful strong, but I had a lifetime of scrubbing and lifting and hard work behind me, and I threw her off—

—Out the open window. I rushed to it, hoping to see her crushed on the stone below, but she was clinging to the brick, clinging with needle-sharp nails. Her pale face grinned up at me, and I screamed; she laughed and scuttled away down the wall like a black-shelled beetle.

I ducked back in and slammed the window sash and bent to help Penny to her feet. That was when I heard the crash of glass, and the screams.

You know how it ended, I suppose. Poor Mrs. Westenra's heart gave out. Miss Lucy's own letter says a dog came through her window, though I never saw it; we found her lying pale and gray on the bed with her mother dead beside her. Penny, Kate, Alice, and I did the best we cold—covered the broken window, wrapped Mrs. Westenra in blankets, and took Miss Lucy downstairs away from the horror.

"Mother," she kept crying, and wanted to go back. But there wasn't no use in it, and besides she was too weak. I took everyone into the withdrawing room and found the liquor cabinet standing open. The brandy was empty—George, no doubt, which would explain the wrecked carriage—but the sherry was still full. I poured everyone a stiff measure, and we sat close to Miss Lucy while she wept. A sip or two of sherry was all she would take, though the rest of us drank up willingly enough; Penny even gulped down what Miss Lucy wouldn't.

"What'll we do, Mary Margaret?" Penny asked, her eyes huge and terrified. She had a wound on her neck like Miss Lucy's, but she didn't seem the worse for it. Just tired.

"We'll stay here," I said. "Let morning come, and Dr. Van Helsing arrive, before we do anything more. Here, Miss Lucy. Are you warm enough?"

She was shivering, poor thing, though we'd wrapped her up. I felt warm enough. Over-warm, perhaps. Time passed, as time does even in the worst of circumstances; Miss Lucy wept, and we tried to comfort her.

It must have been near an hour later when I looked up and found Alice curled asleep in a red Moroccan chair. Kate had nodded off, too. As I watched, Penny dropped her glass and sank down on the fainting couch, her long dark hair spilling over the carpet.

My legs felt weak. When I tried to rise from where I sat, I found I couldn't. My arms had gone numb, and I could feel it stealing through me now like a cold wind.

Laudanum, to put us fast asleep.

"Miss Lucy?" I whispered. She didn't seem to hear me. The door of the withdrawing room opened without even a creak, and there in the dark stood Elizabeth Gwydion.

"Come," she said to Miss Lucy. And Miss Lucy, who hadn't but touched the sherry, wandered away, leaving the blankets on the floor. I couldn't follow, couldn't master my own legs enough to try.

Elizabeth came straight to me and looked me right in the eyes, grinning like a skull, and said, "My master's seeing to your Miss Lucy. But it's my privilege to see to you, you meddling cur."

I started to pray then, because I didn't think I could move. The world was going gray, the edges fraying, and she bent close to me, her lips cold on my neck, sucking like a baby at the breast, and I knew in the next instant she'd bite, and suck blood like red milk. I'd never feared anything so much, never felt such despair.

Something in my robe's pocket felt hot against me. Hot as the sun. Holy Mary.

Mrs. Westenra's paper knife! I grabbed it and stabbed for her, not able to feel my hand, nor the shock when it hit. I only knew I'd made the target when I saw her eyes go wide and strange, saw her stumble back from me and sit down clumsily on the floor with her legs splayed.

The hilt of the silver paper knife glittered on her black dress. I'd pinned it to her heart. She looked amazed.

"You—you English dog—"

"Irish," I snapped.

She was still trying to understand that when she died. Yes, I killed her—but here's the thing, Nora: as she died, she turned to ashes. Ashes, no different than you'd sweep up out of the grate in the morning. Ashes that stirred in the breeze of the door swinging open again.

Her master stood there, looking at the mess I'd made of Elizabeth Gwydion, and his lips drew back from his teeth. His face was ruddy now, his lips smeared with blood, and I thought of Miss Lucy with a terrible sick pang. I didn't have the knife anymore, I had nothing to protect me but my small crucifix and my fear.

"You've killed my servant," he said in some surprise.

"I'd kill her again if she'd get up," I said tartly. "Miss Lucy—"

"Is none of your concern." He walked around me, staring at me with red-flecked eyes. Like a lion that wasn't quite hungry enough to pounce. "I could kill you all tonight."

I couldn't think of any reason he wouldn't. Penny, Kate, Alice… all helpless. Me only a breath away from it. The laudanum was a thick black pool in me, and I was drowning in it.

"Go ahead," I said, as if I didn't even care. "If you'd stoop so low."

He smiled at me then, Dracula did. "For you, I might bend my principles, little one. Or make you my own."

"Go to Hell!"

I shot back, amazed at my own bravery. I'd never cursed in my life, not like that, certainly not to a man. And still he smiled.

"Soon," he promised. "The dead travel fast."

I felt my knees buckle then, and I fell, face down in the ashes of Elizabeth Gwydion. I rolled over, spitting out the bitterness of her, and saw him looking down at me from such a far, far distance. His cold fingers caressed my face.

"No," he said. "I don't think I will do you the favor of killing you. Explain this tomorrow, to your betters. Explain your drunkenness and your dead mistress. Perhaps I'll come to kill you when you're starving on the streets."

His words struck fear in me, absolute fear, because he was right. I fought the dark as he walked away, but there was nothing I could do but fall. I dreamed, you know. This time no adders, no abbeys, no pale wasting ladies. This time I dreamed I was in a great cathedral, and I lit a candle to the smiling statue of Mary, and I prayed.

I prayed until the morning, when Dr. Seward arrived at the house and found Mrs. Westenra dead and Miss Lucy dying.

No, no, I'm all right. A fleck of coal dust in my eye, most likely. But it was a sad house, very sad. And no one to blame it on but four drunken servants, which Dr. Seward promptly did, though of course later he said he knew all along we'd been drugged.

It was Dr. Van Helsing who came to our rescue, finding positions for Kate and Alice. Dr. Van Helsing himself who gave me and Penny posts here in his house. Do you know what he said to me, Nora? He said, "There are monsters all around us, Mary Margaret. Some that people in my position will never see, but perhaps you will."

So here I am. Doing the same ironing, the same scrubbing, the same sweeping. Some things never change, as I said. And some do.

Yes, that one's good. Hand me the next. Now, you must put a good sharp point on them, Nora. Sharp enough to pierce skin like butter. It's got to go right to the monster's heart, you see? Dr. Van Helsing and the others are going after Dracula, but like I told you, this has nothing to do with Dracula. It's below stairs business.

Poor Penny's lying in her coffin in the parlor, waiting on the undertaker. And she were bitten by Dracula that night at Hillingham. If she wakes, we've got to do for her like the Doctor did for Miss Lucy. Test the knife. Sharp enough to cut bone?

Oh, wipe your tears, girl. And say your prayers. There's plenty below stairs who might need the same mercy, before this is all said and done.

We care for our own.

Dear Mr. Bernard Shaw

Judith Proctor

1st October 1893

22 Barkston Gardens

Earls Court, S.W.

Dear Mr. Bernard Shaw,

I write to you because I'm not quite sure who else to write to. You, I am sure, will tell me honestly and fully what you believe of these circumstances. I know you well enough to know that you will not gloss over anything in your reply and that if you feel I am being foolish, you will be blunt enough to tell me.

Be the critic for me once more and tell me if this speaks to you of something possible or simply an overactive imagination on my part. You're as firmly grounded in the real world as anyone I know— your play last year on slum landlords had all of London talking—usually to tear your name to shreds.

I'm wandering off the topic—I'm even being serious—perhaps that tells you how much this has distressed me!

We're playing King Lear. You know that anyway… You see, I'm still dithering.

To begin—for I shall never get going if I don't—it started about two weeks ago. I think it was Wednesday, though it might have been Thursday.

Partway through the play, I became aware of someone in one of the boxes. Now that's nothing unusual. We've been playing to virtually full houses most nights and the boxes are popular. You wouldn't believe what people sometimes get up to in the boxes— the play must be quite a distraction to them. This man was watching the play though. He wasn't just watching it, he was virtually mesmerised. You'd think he'd never been to the theatre before. Henry was giving a bravura performance as Lear and I was doing pretty well myself. I'm really too old to play Cordelia now, but when the audience believes in it, I believe in it too. It's a conspiracy between us and as long as they keep paying to see me, I'm happy to oblige.

The box made him hard to see in the darkness, but I knew he was there—I could feel him.

Last week, he was back haunting me again. That was definitely a Monday. It's easier to get tickets at short notice on Monday, because we're rarely full then. Same seat—he obviously preferred the boxes. There was something so intense about him—like a traveller in a desert who'd finally reached an oasis. He wasn't just thirsty—he was desperate. Something was different this time though, he wasn't watching Henry, he was watching me. Just me.

I've been watched before—you get all sorts in theatres. Some can get a little obsessed. This wasn't the normal admirer hanging over the balcony though. He kept back, and I could barely see him beyond the shadow of the box. I couldn't get a chance to look properly at him; I have to concentrate on the part when I'm performing. It's so easy to become distracted—sometimes the slightest thing can throw me and I lose my lines.

That's what was so strange—I knew he was watching me even when I couldn't see him. Have you ever had that sensation? The feeling of eyes looking at the back of your neck?

I'd swear his eyes were red, but it was probably just a trick of the limelight.

I never did get a good look at his face. Even when he stood to applaud at the end, he was still in the darkness. All I could really tell was that he seemed to be well-dressed; he looked like a man with money.

Actually, that's probably how he got along to Henry's post-show supper a few days later. Bram Stoker—Henry's manager— ' has a real nose for possible investors. He does all Henry's correspondence and I honestly don't know where Henry would be without him. He corresponds with theatres for us, arranges tours, and leaves Henry free to do what he does best—acting.

I knew the stranger was there the moment I entered the room. He stood out in the crowd, there was a space around him and you don't normally get much of that at Henry's parties. I'll try and describe him for you, though memory may make him more dramatic than he actually was. He was tall, almost six foot in height. He'd a real beak of a nose—you could have cast him as Julius Caesar any day—a black moustache, a pointed beard, and a hard cruel face. His teeth were pointed—like a dog's canines. I didn't like the look of him at all.

He became aware of me immediately. Coming over to me, he bowed. "May I introduce myself, Miss Terry? Count Dracula."

He had a European accent, though I couldn't place where from. It certainly wasn't French or German. I really didn't fancy talking to him, but one has to make the effort. One is expected to sparkle at such affairs, so sparkle one does.

I made him feel welcome and asked him where he was from. He wasn't too pleased at that.

"You can tell I am not English?"

"You do have rather a strong accent," though I hastened to add, "but your command of our language is superb. You have obviously studied for many years."

That seemed to mollify him a little. "I wish to come among you as a gentleman, a man of learning. I have no desire to be taken for an inferior."

Well, I had his measure now. "That could never be," I assured him. "Your clothing, your manner, and your speech all declare you to be a nobleman by birth."

Now he was happy—positively preened himself. "The clothing is fashionable? I read your newspapers, but they are short of information on reliable tailors. I do not entirely trust tradesmen who advertise. I asked my legal representatives to recommend a firm to me."

I looked him up and down. You can't make a silk purse out of a sow's ear, but they'd certainly done their best. The cloth draped in the way that only really expensive fabrics do and the cut was excellent. "You must tell me the name of your firm," I said. "If their legal advice is as good as their choice in tailors, I might need them some day."

"I sent m

y measurements in advance; my wardrobe was waiting for me when I arrived."

I still didn't like him, but he was beginning to impress me. He certainly planned carefully enough—he'd never have made an actor. He'd also dodged my question, although I didn't think about that until later. Maybe he would have made an actor after all.

Loretta waved at me from the other side of the room and I tried to make my excuses to go and join her, but Dracula simply took no notice. He had that kind of natural arrogance that comes from having people leap to do your bidding all your life. At least he was polite about it—well, more or less.

"Miss Terry, I must speak to you about the play. Why is it different from what I have read?"

"Didn't the reviews do us justice?"

"You misunderstand me. The play was not performed as it was written. Why did you change the words of Shakespeare?" (You know, you'd have loved him. You're always criticising Henry's version of Shakespeare. You ought to be a theatre critic instead of shredding musicians.)

"A play is a complex thing…"I began, when Bram came to my rescue. Or Henry's rescue if you look at it another way. I really believe that Henry has no more devoted fan than Bram Stoker.

"Henry Irving is a creative genius!" Bram declared. "The words written by a playwright are just the starting point. There is nothing sacrosanct about them. They are clay to be taken and moulded by an actor to suit his needs."

"I have re-read the play," the count declared. "Mr. Irving has changed the words. He has got them wrong."

Whoops… Beard not the lion in his lair… (Do lions have beards?)

Bram exploded. When a six-foot-two, twelve-stone Irishman explodes, you tend to know it.

"Have you no soul!"

The count took an abrupt step back in the face of that fury.

"Don't you know genius when you see it? Henry Irving breathes life into cold words. He puts passion where there was only paper. There isn't his equal on the whole of the British stage."

Dracula's protest was washed away in the onslaught. (I really do think you might have felt quite sorry for the poor man.)

I, Strahd: The War Against Azalin

I, Strahd: The War Against Azalin P N Elrod Omnibus

P N Elrod Omnibus Bloodlist

Bloodlist I, Strahd: The Memoirs of a Vampire

I, Strahd: The Memoirs of a Vampire Lifeblood

Lifeblood Song in the Dark

Song in the Dark The Vampire Files, Volume One

The Vampire Files, Volume One Fire In The Blood

Fire In The Blood Lady Crymsyn

Lady Crymsyn Dark Road Rising

Dark Road Rising The Adventures of Myhr

The Adventures of Myhr Dracula_in_London

Dracula_in_London Cold Streets

Cold Streets The Dark Sleep

The Dark Sleep The Vampire Files, Volume Two

The Vampire Files, Volume Two Blood on the Water

Blood on the Water The Vampire Files Anthology

The Vampire Files Anthology The Vampire Files, Volume Four

The Vampire Files, Volume Four A Chill In The Blood

A Chill In The Blood Bloodcircle

Bloodcircle Art In The Blood

Art In The Blood The Vampire Files, Volume Three

The Vampire Files, Volume Three The Devil You Know

The Devil You Know Hex Appeal

Hex Appeal Jonathan Barrett Gentleman Vampire

Jonathan Barrett Gentleman Vampire Quincey Morris, Vampire

Quincey Morris, Vampire Strange Brew

Strange Brew Lady Crymsy

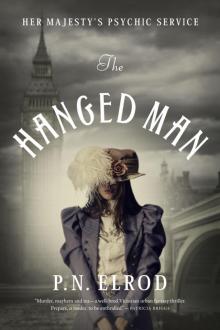

Lady Crymsy The Hanged Man

The Hanged Man