- Home

- P. N. Elrod

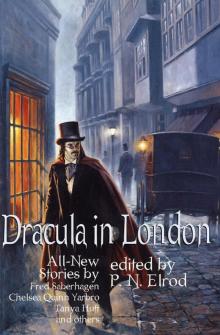

Dracula_in_London Page 2

Dracula_in_London Read online

Page 2

There had been little imagination involved in the naming of the green salon, for the walls were covered in a brocaded green wallpaper that would have been overwhelming had it not been covered in turn by dozens of paintings. A few were surprisingly good, most were indifferent, and all had been placed within remarkably ugly frames. The furniture had been upholstered in a variety of green and gold and cream patterns and underfoot was a carpet predominantly consisting of green cabbage roses. Everything that could be gilded, had been. Suppressing a shudder, he was almost overcome by a sudden wave of longing for the bare stone and dark, heavy oak of home.

Small groups of people were clustered about the room, but his eyes were instantly drawn to the pair of facing settees where half a dozen beautiful women sat talking together, creamy shoulders and bare arms rising from silks and satins heavily corseted around impossibly tiny waists. How was it his newspapers had described the women to be found circling around the prince? Ah yes, as "a flotilla of white swans, their long necks supporting delicate jeweled heads." He had thought it excessively fanciful when he read it but now, now he saw that it was only beautifully accurate.

"We'll introduce you to the ladies later," March murmured, leading the way across the center of the room. "That's His Highness by the window."

Although he would have much preferred to take the less obvious route around the edges, the Count followed. As they passed the ladies, he glanced down. Most were so obviously looking away they could only have been staring at him the moment before, but one met his gaze. Her eyes widened and her lips parted but she did not look away. He could see the pulse beating in the soft column of her throat. Later, he promised, and moved on.

"Your Royal Highness, may I present a recent acquaintance of mine, Count Dracula."

Even before March spoke, he had identified which of the stout, whiskered men smoking cigars by the open window was Edward, the Prince of Wales. Not from the newspaper photographs, for he found it difficult to see the living in such flat black and gray representations, but from the nearly visible aura of power that surrounded him. Like recognized like. Power recognized power. If the reports accompanying the photographs were true, the prince was not allowed much in the way of political power but he was clearly conscious of himself as a member of the royal caste.

He bowed, in the old way, body rigid, heels coming together. "I am honored to make your acquaintance, Your Highness."

The prince's heavy lids dropped slightly. "Count Dracula? This sounds familiar, yah? You are from where?"

"From the Carpathian Mountains, Highness," he replied in German. His concerns about sounding foreign had obviously been unnecessary. Edward sounded more like a German prince than an English one. "My family has been boyers, princes there since before we turned back the Turk many centuries ago. Princes still when we threw off the Hungarian yoke. Leaders in every war. But…" He sighed and spread his hands. "… the warlike days are over and the glories of my great race are as a tale that is told."

"Well said, sir!" the prince exclaimed in the same language. "Although I am certain I have heard your name, I am afraid I do not know that area well—as familiar as I am with most of Europe." He smiled and added, "As related as I am to most of Europe. If you are not married, Dracula, I regret I have no sisters remaining."

The gathered men laughed with the prince, although the Count could see not all of them—and Mr. March was of that group—spoke German. "I am not married now, Your Highness, although I was in the past."

"Death takes so many," Edward agreed solemnly.

The Count bowed again. "My deepest sympathies on the death of your eldest son, Highness." The report of how the Duke of Clarence had unexpectedly died of pneumonia in early 1892 had been in one of the last newspaper bundles he'd received. As far as the Count was concerned, death should be unexpected, but he was perfectly capable of saying what others considered to be the right thing. If it suited his purposes.

"It was a most difficult time," Edward admitted. "And the wound still bleeds. I would have given my life for him." He stared intently at his cigar.

With predator patience, the Count absorbed the silence that followed as everyone but he and the prince shifted uncomfortably in place.

"Shall I tell you how I met the Count, your Highness?" March asked suddenly. "There was a bully smash up on Piccadilly."

"A bully smash up?" the prince repeated lifting his head and switching back to English. "Were you in it?"

"No, sir, I wasn't."

"Was the Count?"

"No sir, he wasn't either. But we both saw it, didn't we, Count?"

The Count saw that the prince was amused by the American so, although he dearly wanted to put the man in his place, he said only, "Yes."

"And you consider this accident to be a gutt introduction to a Carpathian prince?" Edward asked, smiling.

If March had possessed a tail, the Count realized, he'd have been wagging it; he was so obviously pleased that he'd lifted the Prince of Wales's spirits. "Yes, sir, I did. Few things bring men together like disasters. Isn't that true, Count?"

That, he could wholeheartedly agree with. He was introduced in turn to Lord Nathan Rothschild, Sir Ernest Cassel, and Sir Thomas Lipton—current favorites of Prince Edward—and he silently thanked the English newspapers and magazines that had provided enough facts about these men for him to converse intelligently.

He was listening with interest to a discussion of the Greek-Turkish War when he became aware of Mr. March's scrutiny. Turning toward the American, he caught the pudgy man's gaze and held it. "Yes?"

March blinked, and the Count couldn't help thinking that even the horse on Piccadilly hadn't taken so long to recognize its danger. It wasn't that March was stupid—it seemed that old terrors had been forgotten in his new land.

"I was just wondering about your glasses, Count. Why do you keep those smoked lenses on inside?"

Because the prince was also listening, he explained. "My eyes are very sensitive to light and I am not used to so much interior illumination." He gestured at the gas lamps. "This is quite a marvel to me."

Prince Edward beamed. "You will find England at the very front of science and technology. This…" he echoed the Count's gesture, trailing smoke from his cigar, "is nothing. Before not much longer we will see electricity take the place of gas, motor cars take the place of horses, and actors and actresses…" his smile was answered by the most beautiful of the women seated across the room, "replaced by images on a screen. I, myself have seen these images—have seen them move— right here in London. The British Empire shall lead the way into the new century!"

Those close enough to hear applauded, and March shouted an enthusiastic "Hurrah!"

The Count bowed a third time. "It is why I have come to London, Highness; to be led into the new century."

"Gutt man." A footman carrying a tray of full wine glasses appeared at the prince's elbow. "Please try the burgundy, it is a very gutt wine."

About to admit that he did not drink wine, the Count reconsidered. In order to remain un-noted, he must be seen to do as others did. "Thank you, Highness." It helped that the burgundy was a rich, dark red. While he didn't actually drink it, he appreciated the color.

When the clock on the mantle struck nine, Edward led the way to the card room, motioning that the Count should fall in beside him. "Have you seen much of my London?" he asked.

"Not yet, Highness. Although I was at the zoo only a few days past."

"The zoo? I have never been there, myself. Animals I am most fond of, I see through my sights." He mimed shooting a rifle and again his immediate circle, now walking two by two down the hall behind him, laughed.

"And he'd rather see a good race than govern, wouldn't you, Highness?" Directly behind Edward's shoulder, March leaned forward enough to come between the two princes. "Twenty-eight race meetings last year. I heard that's three more visits than he made to his House of Lords."

The Count felt the Prince of Wales stiffen beside him. B

efore the prince could speak, the Count turned and dipped his head just far enough to spear March over the edge of his glasses. "It is not wise," he said slowly, "to repeat everything one hears."

To his astonishment, March smiled. "I wouldn't repeat it outside this company."

"Don't," Edward advised.

"You betcha," March agreed. "Say, Count, your eyes are kind of red. My missus has some drops she puts in hers. I could find out what they are if you like."

Too taken aback to be angry, the Count shook his head. "No. Thank you."

Murmuring, "Lovely manners," in an approving tone, March stepped forward so that he could open the card room door for the prince.

"He is rough, like many Americans," Edward confided in low German as they entered. "But his heart is gutt and, more importantly, his wallet is deep."

"Then for your sake, Highness…"

The game in the card room was bridge and Prince Edward had a passion for it. After two hours of watching the prince move bits of painted card about, the Count understood the attraction no better than he had in the beginning.

Just after midnight, the prince gave his place to Sir Thomas.

"It was gutt to meet you, Count Dracula. I hope to see you again."

"You will, Highness."

Caught and held in the red gaze, the prince wet full lips and swallowed heavily.

One last time, the Count bowed and stepped back, breaking his hold.

Breathing heavily, Edward hurried from the room. A woman's laughter met him in the hall.

The Count turned to the table. "If you will excuse me, gentlemen, now that His Highness has taken his leave, I will follow. I am certain that I will see you all again."

In the foyer, only for the pleasure of watching terror blanch the boy's cheek, he brushed the footman's hand with his as he took back his gloves.

He very nearly made it out the door.

"Say, Count! Hold up and I'll walk with you." March fell into step beside him as he crossed the threshold back into the night. "It's close in those rooms, ain't it? September's a lot warmer here than it is back home. Where are you heading?"

"To the Thames."

"Going across to the fleshpots in Southwark?" the American asked archly.

"Fleshpots?" It took him a moment to understand. "No. I will not be crossing the river."

"Just taking a walk on the shore then? Count me in."

They walked in blessed silence for a few moments, along Pall Mall and down Cockspur Street.

"His Highness likes you, Count. I could tell. You have a real presence in a room, you know."

"The weight of history, Mr. March."

"Say what?"

He saw a rat watching him from the shadow, rat and shadow both in the midst of wealth and plenty, and he smiled. "It is not necessary you understand."

Silence reigned again until they reached the riverbank.

"You seemed to be having a good time tonight, Count." March leaned on the metal railings at the top of the embankment. "Didn't I tell you they were your kind of people?"

"Yes."

"So." A bit of loose stone went over the edge and into the water. "Did you want to go somewhere for a bite?"

"That won't be necessary." He removed his glasses and slid them carefully into an inside pocket. "Here is fine."

The body slid down the embankment and was swallowed almost silently by the dark water. Replete, the Count drew the back of one hand over his mouth then stared in annoyance at the dark smear across the back of his glove. These were his favorite gloves; they'd have to be washed.

He turned toward home, then he paused.

Why hurry?

The night was not exactly young, but morning would be hours still.

As he walked along the riverbank toward the distant sound of voices, he smiled. The late Charlie March had not been entirely correct. The prince and his company were not exactly his kind of people…

… yet.

Box Number Fifty

Fred Saberhagen

Carrie had been living on the London streets for a night and a day, plenty of time to learn that being taken in charge by the police was not the worst thing that could happen. But it would be bad enough. What she had heard of the conditions in which homeless children were confined made her ready to risk a lot in trying to stay free.

A huge dray drawn by two whipped and lathered horses rushed past, almost knocking her down, as she began to cross another street. Tightening her grip on the hand of nine-year-old Christopher as he stumbled in exhaustion, she struggled on through the London fog, wet air greasy with burning coal and wood. Around the children were a million strangers, all in a hurry amid an endless roar of traffic.

"Where we going to sleep tonight?" Her little brother sounded desperate, and no doubt he was. Last night they had had almost no sleep at all, huddled against the abutment of a railway bridge; hut fortunately it had not been raining then as it was now. There had been only one episode of real adventure during the night, when Chris, on going a little way apart to answer a call of nature, had been set on and robbed of his shoes by several playful fellows not much bigger than he.

Their wanderings had brought them into Soho, where they attracted some unwelcome attention. Carrie thought that a pair of rough-looking youths had now begun to follow them.

She had to seek help somewhere, and none of the faces in her immediate vicinity looked promising. On impulse she turned from the pavement up a flight of stone steps to the front door of a house. It was a narrow building of gray stone, not particularly old or new, one of a row, wedged tightly against its neighbors on either side. Had Carrie been given time to think about it, she might have said that she chose this house because it bore a certain air of quiet and decency, in contrast to its neighbors, which at this early stage of evening were given to lights and raucous noise.

Across the street, a helmeted bobby was taking no interest in a girl and boy with nowhere to go. But he might at any moment. These were not true slums, not, by far, the worst part of London. Still, here and there, in out-of-the-way corners, a derelict or two lay drunk or dying.

Carrie went briskly up the steps to the front door, while her brother, following some impulse of his own, slipped down into the areaway where he was for the moment concealed from the street. Glancing quickly down at Christopher from the high steps, Carrie thought he was doing something to one of the cellar windows.

Giving a long pull on the bell, she heard a distant ringing somewhere inside. And at the same moment, she saw to her dismay that what she had thought was a modest light somewhere in the interior of the house was really only a reflection in one of the front windows. There were curtains inside, but other than that the place had an uninhabited look and feel about it.

"Not a-goin' ter let yer in?" One of the youths following her had now stopped on the pavement at the foot of the steps, where he stood grinning up at her, while his fellow stood beside him, equally delighted.

"I know a house where you'd be welcome, dear," called the second one. He was older, meaner-looking. "I know some good girls who live there."

Turning her back on them both, she tried to project an air of confidence and respectability, as she persisted in pulling at the bell.

"My name's Vincent," came the deeper voice from behind her. "If maybe you need a friend, dearie, a little help—"

Carrie caught her breath at the sound of an answering fumble in the darkness on the other side of the barrier—and was mightily relieved a moment later when her brother opened the door from inside. In a moment she was in, and had closed and latched the door behind her.

She could picture the pair who had been heckling her from the pavement, balked for the moment, turning away.

It was so dark in the house that she could barely see Christopher's pale face at an arm's-length distance, but at least they were no longer standing in the rain.

"How'd you get in?" she whispered at him fiercely. Then, "Whose house is this?"

"Broke

n latch on a window down there," he whispered back. Then he added in a more normal voice, "It was awful dark in the cellar; I barked my shin on something trying to find the stair."

It was a good thing, Carrie congratulated herself in passing, that neither of them had ever been especially afraid of the dark. Already her eyes were growing accustomed to the deep gloom; enough light strayed in from the street, around the fringes of curtain, to reveal the fact that the front hall where they were standing was hardly furnished at all, nor was the parlor, just beyond a broad archway. More clearly than ever, the house said empty.

"Let's try the gas," she whispered. Chris, fumbling in the drawer of a built-in sideboard, soon came up with some matches. Carrie, standing on tiptoe, was tall enough to reach a fixture projecting from the wall. In a moment more she had one of the gaslights lit.

"Is anyone here?" Now her voice too was up to normal; the answer seemed to be no. The sideboard drawer also contained a couple of short scraps of candle, and soon they had lights in hand to go exploring.

Front hall, with an old abandoned mirror still fastened to the wall beside a hat rack and a shelf. Just in from the hall, a wooden stair, handrail carved with a touch of elegance, went straight up to the next floor. Not even a mouse stirred in the barren parlor. The dining room was a desert also, no furniture at all. And so, farther back, was the kitchen, except for a great black stove and a sink whose bright new length of metal pipe promised running water. An interior cellar door had been left open by Chris in his hurried ascent, and next to it a recently walled-off cubicle contained a water closet. A kitchen window looked out on what was no doubt a back garden, now invisible in gloom and rain.

Carrie was ready to explore upstairs, but Christopher insisted on seeing the cellar first, curious as to what object he had stumbled over. The culprit proved to be a cheaply constructed crate, not quite wide or long enough to be a coffin, containing only some scraps of kindling wood. Otherwise the cellar—damp brick walls; floor part pavement, part dry earth—was as empty as the house above.

I, Strahd: The War Against Azalin

I, Strahd: The War Against Azalin P N Elrod Omnibus

P N Elrod Omnibus Bloodlist

Bloodlist I, Strahd: The Memoirs of a Vampire

I, Strahd: The Memoirs of a Vampire Lifeblood

Lifeblood Song in the Dark

Song in the Dark The Vampire Files, Volume One

The Vampire Files, Volume One Fire In The Blood

Fire In The Blood Lady Crymsyn

Lady Crymsyn Dark Road Rising

Dark Road Rising The Adventures of Myhr

The Adventures of Myhr Dracula_in_London

Dracula_in_London Cold Streets

Cold Streets The Dark Sleep

The Dark Sleep The Vampire Files, Volume Two

The Vampire Files, Volume Two Blood on the Water

Blood on the Water The Vampire Files Anthology

The Vampire Files Anthology The Vampire Files, Volume Four

The Vampire Files, Volume Four A Chill In The Blood

A Chill In The Blood Bloodcircle

Bloodcircle Art In The Blood

Art In The Blood The Vampire Files, Volume Three

The Vampire Files, Volume Three The Devil You Know

The Devil You Know Hex Appeal

Hex Appeal Jonathan Barrett Gentleman Vampire

Jonathan Barrett Gentleman Vampire Quincey Morris, Vampire

Quincey Morris, Vampire Strange Brew

Strange Brew Lady Crymsy

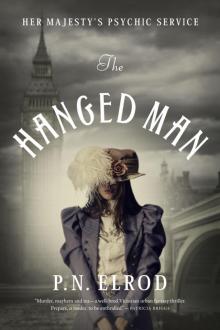

Lady Crymsy The Hanged Man

The Hanged Man