- Home

- P. N. Elrod

The Devil You Know Page 2

The Devil You Know Read online

Page 2

Barrett clicked on a table lamp. The twenty-five watt bulb was good enough lighting for my sensitive eyes, but the corners remained stubbornly gloomy. Since books crowded the shelves on two walls I decided to risk calling this place a library, though odds favored there was another, bigger one lurking elsewhere in the joint.

“Make yourself at home, I’ll get some refreshment,” he said.

I knew what that would be, but the “getting” part stumped me. He kept horses, both for riding and to provide a steady, ongoing supply of fresh blood. Was he going to bring one in the house for the convenience of his guest?

He excused himself and went off. I wanted to get some questions out of the way, but he’d been raised in a time where civilized customs were followed come hell or high water. A faint echo of such old-time courtesies remained in some homes. My mother couldn’t imagine having guests over without first making sure they each had a cup of coffee and a plate of cookies at hand.

I wandered and read book titles. A few I recognized, but the rest were well before my time. The once important issues in the nonfiction works were either stale with age or about the kind of problem that’s never resolved. I opened a few to check printing dates, finding none more recent than 1890. Barrett didn’t look it, but the man was old.

Was this my future? If I got to be his age would I wind up with a house full of irrelevant books gathering dust?

Against expectation I found an overstuffed chair suitable for wallowing and tried to relax in it. The silence of the house pressed down, and I listened hard for any sign of activity. Except for a distant scuffing of slipper-clad feet and the slam of a door—my host going outside—nothing. Where was everybody?

Unpleasant words like mausoleum and tomb trundled through my brain. I vowed that if I ever got Emily Francher’s kind of wealth I would never inflict such a massive house on myself. This place gave me the creeps, which was saying something.

The chair abruptly ceased to be comfortable and turned into a smothering monster, which was crazy since I don’t have to breathe regularly. I struggled free and went to the room’s one window to pull open the curtain, revealing a long stretch of shaded veranda. It would be a pleasant place to lounge in the summer, but the fair weather furniture was stacked off to the side, some of it covered by a tied down tarp. Another batch was unadorned, though lengths of cut rope from its missing tarp lay on the flagstones like dead snakes.

A few steps down from the shaded area was a swimming pool, drained for the winter. Though bleak with snow and blown-in debris, it didn’t take much to remember young Laura Francher doing laps in that pool, her long blond hair streaming gracefully behind as she swam.

I have to stop doing this to myself.

I resisted letting the curtain drop on the memory and looked beyond the pool, seeking some hint of life on the estate.

The stables and horses weren’t within view, though there was a distant slice of twinkling gray that marked the Sound. I could see myself strolling down there to look at the water when the weather was fine. Not that I didn’t have the same opportunity in Chicago, but Lake Michigan wasn’t Long Island Sound. There’s a difference, and if I put some thought to it I might figure it out, but not tonight.

I now let the curtain fall and checked the room again. No changes had taken place in the last minute; the old books stared back, lonely and bored. I recalled there being a radio in one of the other ground floor rooms, but wasn’t desperate enough to go looking.

With some relief I heard a door bang shut, followed by dish-clattering sounds. What was he doing? Or maybe it was someone else in the house . . . nope, same slippers scuffing, then a rattling and the squeak of rubber on the marble tiles, like a wheelchair. I couldn’t help but think of Maureen’s crazy sister.

This place was really getting to me.

Barrett came in, pushing an innocuous tea trolley.

I hid my relief, replacing it with brief puzzlement. A teapot, cups, and saucers were on the trolley.

At his gesture, I found a chair. He sat opposite and poured from the pot, prim as an old maid on Sunday. He offered me a teacup filled with still-warm blood.

It was the damnedest thing I’d seen in at least a week.

“Is it all right?” he asked.

“Uh . . . ”

“Sorry, I should have inquired first. I assumed you might be hungry after your trip.”

“It’s great, really. I just never thought of having it like this.”

“Never?” He poured a cup for himself. “You prefer to take it on the hoof?”

“Uh. . .lately I buy a quart or two at the butcher and keep it in beer bottles in the ice box.”

“Doesn’t it go bad rather quickly?”

“I drink it off too fast. Saves trips to the Stockyards when I get busy.” The teacup had painted-on flowers, liberal gold edging, and I felt like an over-ripe sissy sipping from it.

Barrett didn’t seem to have the same problem. The delicate porcelain looked natural in his hands, not at all awkward. He finished half his portion and gave a little sigh of satisfaction.

On that we agreed. The horse blood—I knew the taste—was very good.

“Is Haskell still here?” I asked. He’d been in charge of the horses and had helped me draw blood from them in a hasty effort to save Barrett’s life.

“Yes, but he’s away on holiday along with the other servants. It seemed best to not have them around for the time being. We’re quite on our own.”

With interest I saw the whites of his eyes flushing deep red as the blood spread through him. Mine would look the same. “Miss Francher’s gone, too?”

“Yes. Away shopping.”

There’d been a slight hesitation to that yes. “Shopping?”

“Off in the city. Dress fittings and such, see some movies, take in a few plays.”

I drained off my cup and managed to put it and the saucer back on the trolley without breaking either. “You’re a piss-poor liar, Barrett.”

He snapped a glare my way, shoulders and spine stiffening. “I am no liar, sir.” But he didn’t challenge me to a duel, so I was on the right track.

“You left something out, though.”

“Emily has gone to the city, as I said.”

“And?”

“None of your damn—” He cut off and shook his head, slumping a little. “Oh, bloody hell.”

The room got quiet since neither of us had a heartbeat. I waited him out.

“What does it matter?” he finally muttered. “You might as well know. She left me.”

The hell? “You’re kidding.”

But his visible pain said it all, explaining his general scruffiness and fatigued manner. “When?”

He grunted, shaking his head.

“But you were together for so long.”

He gave a soft snort. “Not really.”

Yeah, to someone his age those years with her were an eye-blink. “Anything set her off?” Maybe the massive exhumation within sight of the house had been too much.

“This was some while in coming.”

Escott should be here. He was good at this kind of stuff and friends with the man. Barrett barely knew me and wasn’t thrilled about it. Making no comment seemed the best way to get him to talk. In this silent house one of us would have to say something.

He put his cup down, made a fist, and thumped it gently against his chair arm. “The last year has been . . . difficult. But it started before then.”

I made one of those encouraging sounds in the back of my throat.

“The first few weeks after her change to this life were not easy, but we got through it, and things were wonderful for a time. And then it began to fall to pieces so gradually we didn’t see what was happening. We had rows over nothing yet didn’t talk about the real problems. Too afraid to, I suppose. There is a great security to being in love. One does not want to face the terror of its death, so you pretend it is still there, that all is well, that you don’t have to be al

one.”

“Until you can’t take it any longer?”

“Yes. Even so. There comes the point where being alone is not such an unbearable state after all. So she left.”

“That stinks, Barrett. I’m sorry.”

He gave a small shrug. “Thank you. I appreciate your listening.”

“She’s gone for good?”

“She packed for an extended trip, took both maids along to look after her during the day, and went to the city about a month ago. Last week I got a card from some place in Florida so I’d know where to forward their mail.”

“You write to Charles about this? He never said anything.”

“No, I did not. Perhaps when you return you could let him know for me. I haven’t the heart to write. Family laundry, personal business, and all that.”

“Sure. No problem.”

He leaned back in the chair, looking introspective. “Though this is hardly familial. We never married, though I asked her. Just as well that we did not.”

I couldn’t help but feel a tug of sympathy and not a little selfish concern for my own situation. I’d proposed to Bobbi until she’d told me to stop. She loved me, but wasn’t ready to take that step. Though our situation was different from Barrett’s, I couldn’t help but wonder if the same thing might someday happen to us.

That lasted about three seconds, when I came to my senses. Bobbi and I were crazy about each other and had been through too much together. We didn’t have fights, either. It helped that she was usually right about things, while I rarely bothered to form an opinion in the first place.

I tried to recall what I knew about Emily Francher. She was—with her determinedly reclusive nature and predilection for wearing layers of diamonds—eccentric, but hadn’t struck me as being very interesting. Barrett obviously cared for her, but I never saw what the fuss was about. The only spark in her that I’d noticed had come from the jewelry.

She’d been bullied into marriage by her mother, ignored by her husband, and made a young widow not long after. The experience must have soured her on matrimony. Barrett may have overlooked that.

And then what? Years later her young cousin murders her; she wakes up in a coffin, disoriented, not remembering her own death. Barrett had been overjoyed that she’d made the change from dead to undead, but Emily had a hard time taking it in; I’d seen that much in her eyes. Confusion, fear, denial, anger, and who knows what else in those earliest moments when everything you know has been flipped upside down and inside out. The memory of my own difficult resurrection still gave me the heebies.

Escott and I left the next night, assuming Barrett and Emily would live happily ever after. Now I could see where things might have been less than perfect for them. They’d prepared for her possible return, but not Laura’s death and vicious crimes. How had that hit Emily? Did she blame Barrett? Did she blame herself? And why in God’s name had she continued to stay in this oversized museum with its bad memories? She must have decided a winter trip to Florida would blow out the cobwebs.

“She’s coming back, though, right?” I asked.

Barrett shrugged. “I expect she’ll return in the spring, but things are too broken between us to ever repair.”

“You sure?”

“I am. For all that I adore them, women are absolutely maddening, and damn me if I can understand any of them. I do know when one has ceased to love me. I just wish . . . .well, there’s nothing for it, it’s the devil of our condition.”

“What is?”

“That I cannot get roaring drunk and forget about her for a time.”

Actually, he could. If he got enough booze into one of his horses or fed from a drunk human—but I wasn’t going to share that with him. I’d turned into a dangerous lunatic when it’d happened to me.

“So you’re going to stay on here a few more months?” I wanted to change the subject.

“Longer than that. Emily offered me the house. I bought it.”

That bombshell made me blink. First, I didn’t know Barrett had that kind of money, and second, that Emily was capable of doing something so big. Perhaps waking up undead had woken her up in other ways. Suddenly young again, free to go anywhere she liked, and able to do just about anything she wanted without worrying much about consequences—it must have been a hell of an eye-opener.

“You like it here?” I asked, not thinking.

He shot me a strange look, and unexpectedly began to laugh until it turned into a coughing fit. It took another teacup of horse blood to clear his throat. “I should explain—this is my home.” He waved a hand, palm up, indicating a wider area. “The land, I mean. The land belonged to my family long before that damned rebellion forced us to move to England. When I finally came back to see what had become of the holdings I found that it had been confiscated and sold—illegally—to some upstart who wouldn’t part with it.”

“You’ve been after it ever since?”

“Please, I’m no lost heir looking to reclaim my kingdom. I only wanted to make sure it was preserved and not divided up and sold off a bit at a time. Past owners have been sensible about that sort of thing. Those who were not always benefited from a talk with me.”

Which would certainly include a bout of hypnosis. It’s what I’d have done to change someone’s mind.

“It’s why I attended a party years ago in the old house. There had been upheavals in the Francher family and Violet—Emily’s mother—was an unpredictable harpy. I wanted to see what she was up to . . . and then I met Emily and everything changed.”

Great, he looked ready to slump over and start a fresh round of misery. At this point every subject would lead back to Emily. He wasn’t the only one missing the numbing effect of booze.

“You’re going to live in this big place on your own?”

“For the time being. Lord, man, you look horrified. What would you have me do?”

“Get out, go somewhere, and do something.”

“What? Find work? Our nature rather limits our choices, though I understand you’ve done well for yourself. Sir, as I have the means for it, I am content to be a country gentleman until such time as it wearies me. I will not deprive some fellow in greater need by taking his job. In turn, I shall provide employment for a few good-hearted sorts who won’t mind seeing to the more mundane aspects of running this estate in exchange for a fair wage from a lenient master.”

Sitting around with nothing to do but watch someone else polishing the silver would send me straight into the booby-hatch.

Barrett read my face. “That evidently holds no appeal for you, yet you have a nightclub. Charles mentioned it in correspondence. What is it but another version of what I have here? You employ people and oversee something that provides you a goodly amount of pleasure and pride.”

“It earns a living.”

“A minor disparity.”

He was full of spinach, but it was his house, he was my host, and further disagreement would be bad manners. Once in a while, when I made the effort, I could be polite with the best of them.

Besides, I understood what it was like nursing a broken heart. I just didn’t like thinking about it.

I, Strahd: The War Against Azalin

I, Strahd: The War Against Azalin P N Elrod Omnibus

P N Elrod Omnibus Bloodlist

Bloodlist I, Strahd: The Memoirs of a Vampire

I, Strahd: The Memoirs of a Vampire Lifeblood

Lifeblood Song in the Dark

Song in the Dark The Vampire Files, Volume One

The Vampire Files, Volume One Fire In The Blood

Fire In The Blood Lady Crymsyn

Lady Crymsyn Dark Road Rising

Dark Road Rising The Adventures of Myhr

The Adventures of Myhr Dracula_in_London

Dracula_in_London Cold Streets

Cold Streets The Dark Sleep

The Dark Sleep The Vampire Files, Volume Two

The Vampire Files, Volume Two Blood on the Water

Blood on the Water The Vampire Files Anthology

The Vampire Files Anthology The Vampire Files, Volume Four

The Vampire Files, Volume Four A Chill In The Blood

A Chill In The Blood Bloodcircle

Bloodcircle Art In The Blood

Art In The Blood The Vampire Files, Volume Three

The Vampire Files, Volume Three The Devil You Know

The Devil You Know Hex Appeal

Hex Appeal Jonathan Barrett Gentleman Vampire

Jonathan Barrett Gentleman Vampire Quincey Morris, Vampire

Quincey Morris, Vampire Strange Brew

Strange Brew Lady Crymsy

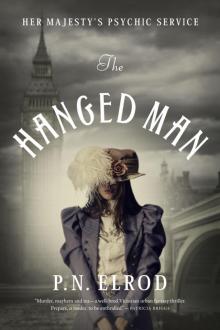

Lady Crymsy The Hanged Man

The Hanged Man